It wasn’t as if the National Hockey League was gripped in an icy version of a civil war; not quite. But when the six club owners convened in Manhattan early in December 1951 it was clear that there were two parties that vehemently disagreed with each other.

On one side were the two Canadian teams — Toronto and Montreal — along with a lone American sextet, the Detroit Red Wings. Combined, they represented what amounted to an old-school conservative bloc. They resisted change, as one reporter noted, because they were coining money left and right.

“All three franchises had very good teams,” according to one analyst, “and played to good crowds. The ‘Haves’ liked things the way they were.”

But factions from Chicago, New York and Boston were conspicuously unhappy. Neither the Black Hawks, Rangers nor Bruins were doing especially well, either artistically or fiscally.

“We needed ways and means to attract more fans,” said Rangers manager Frank Boucher, “and one of them was a return of overtime.

The only reason it had been eliminated was because of wartime restrictions on travel. But that excuse doesn’t hold anymore”

Early in December 1951, the two sides collided at Manhattan’s Park Lane Hotel. I was an 18-year-old Brooklyn College student at the time and was tempted to bust in at the NHL governors meeting to put in my vote for OT.

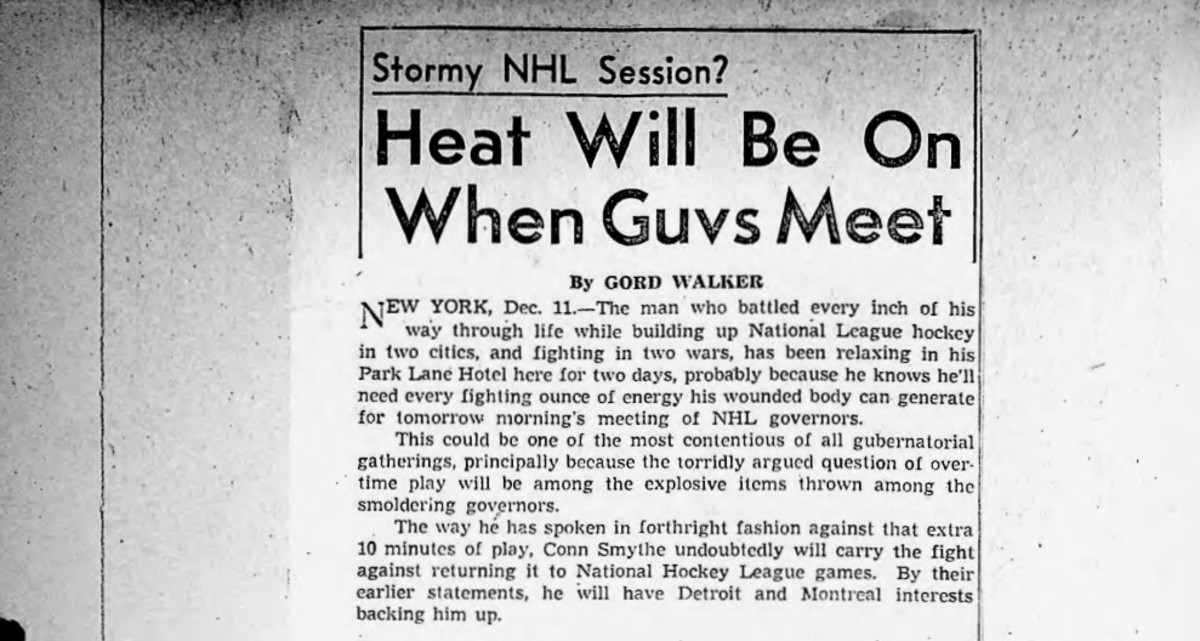

Since that was an impossibility, I relied on the arrival of my daily Toronto Globe and Mail to get a good line on the conflict. The headlines said it all: HEAT WILL BE ON WHEN GUVS MEET.

And: STORMY NHL SESSION?

Reporter Gord Walker was dispatched to cover the meeting and offered the following preview:

“This could be one of the most contentious of all gubernatorial gatherings. principally because the torridly argued question of overtime play will be among the explosive items thrown among the smoldering governors.”

Toronto’s hockey boss, Conn Smythe, was the most vehement opponent to a restoration of an extra session in case of a tie.

Gord Walker: “The way Smythe has spoken in forthright fashion against that extra 10 minutes of play, he undoubtedly will carry the fight against returning it to NHL games.

“The Bruins and Rangers are definitely arrayed against this powerful threesome, and they haven’t minced words about how important they regard this issue in their respective cities.”

But overtime was only one of a few anger-inducing subjects between the “Have” Canadian teams plus Detroit and the trio of American squads.

Leading the lobbying for the Americans, Bruins president Walter Brown infuriated Smythe by demanding a gate-sharing system. His request took the following form:

“Resolved that the visiting team should be given a portion of all gates on the road.”

To which, Smythe shouted back: “That’s nothing but ‘subsidization.’ and I won’t have it.”

(Editor’s Note) History has shown that Smythe’s forces won both battles. A good 32 years elapsed before OT was restored in 1983.

Likewise a “Help The Poor” system was put into play during the late 1950s to assist the less-affluent Black Hawks at the time.)

Smythe remained the NHL’s primary power broker among the owners through the 1950s. His iron-fisted attitude became evident again in February 1957 when an NHL Players’ Association was formed.

“Smythe seemed to take the Players’ Association as a personal attack,” wrote historian Erc Zweig in his oral history of the Maple Leafs.

When Smythe learned that two of his best defensemen — Jim Thomson and Gus Mortson — were involved in union organizing, he took action against them.

“I find it very difficult to imagine that the captain of my club (Thomson) should find time during the season to influence young players to join an organization that has no specific plan to benefit or improve hockey.”

As punishment, Smythe eventually removed the captaincy from Thomson and dealt him to the Black Hawks along with Mortson. At the time, Chicago was considered the Siberia of Hockey.

Other union organizers similarly were exiled. Ted Lindsay and Glenn Hall, from Detroit to Chicago, and Doug Harvey from Montreal to the Rangers. Eventually, the union was quashed.

A decade later the current NHL Players’ Association was formed and this time, survived and thrived.

Coincidentally, the new union was born in 1967, which was the last time the Maple Leafs won The Stanley Cup. Conn Smythe, who died in 1980, was around for the championship celebration

It was the last year of “The Original Six,” a compact league that Smythe desperately tried to maintain but lost to expansion.

This news is republished from another source. You can check the original article here