- In 1969, NASCAR president Bill France refused overtures from drivers about postponing the inaugural race at Talladega to give Firestone and Goodyear time to build tires that could handle the speeds and the new asphalt surface.

- France suggested in a drivers’ meeting they didn’t have to race if they were scared.

- A driver boycott ensued, and Bobby Isaac and former Daytona 500 winner Tiny Lund were the only NASCAR Cup regulars to take the green, as the Xfinity Series drivers of the day completed the field.

Once complete, NASCAR participants agreed the new track built by Bill France near Talladega, Ala., was a thing of beauty.

Its length of 2.66 miles and 33-degree banking would soon lead to qualifying laps that averaged 200 mph. But drivers in NASCAR’s premier Grand National division (today, the Cup Series) could not agree with France about running the first race on Sept. 14, 1969, because tires came apart during the initial practice sessions.

For one brief moment in time, NASCAR came apart as a result.

After a major effort to finish the track on the site of a former Air Force field, France refused any overtures from drivers about postponing the first race to give Firestone and Goodyear time to build tires that could handle the speeds and the new asphalt surface. Long retired from competition, “Big Bill” got into a car and circulated around the track at more than 160 mph to prove it was safe. That was fast for a man on the cusp of his 60th birthday, but slower than what the top teams had been running—or Bobby Isaac’s eventual pole lap of 196.386 mph.

France conducted a meeting in the garage in an effort to persuade drivers. When he suggested they didn’t have to race if they were scared, Lee Roy Yarbrough, the season’s most frequent winner on the faster tracks, stepped up and cold-cocked him. In a later meeting led by Richard Petty outside the track, 36 drivers who had entered elected to pack up and go home, effectively the first driver strike in NASCAR history. The Professional Drivers Association had already been organized a month earlier in Michigan in an attempt to build purses and improve safety. Events at Talladega galvanized the fledging union.

“The Talladega deal came up and everybody said, ‘We’re an organization and we ain’t going to run,” said Petty. “I was the head leader of it and they tell me what they wanted to do and I said, ‘OK.”

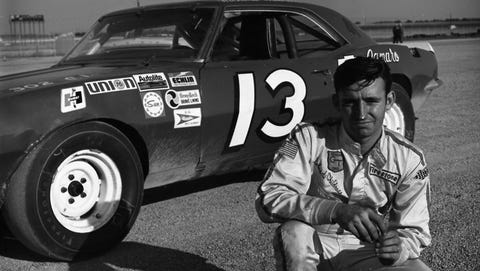

Undaunted, France allowed the drivers from Saturday’s Grand American race to run their cars in Sunday’s feature, despite shorter wheelbases. Bobby Isaac and former Daytona 500 winner Tiny Lund were the only Cup Series regulars to take the green. (Isaac later received a gold watch from France inscribed, “Winners never quit. Quitters never win.”) Richard Childress was among those making their first starts in the Grand National division, gladly taking the bonus offered by France to help buy land for a new race shop.

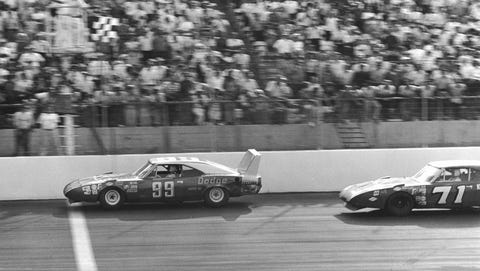

The lead frequently changed hands under green in front of a crowd reported as 62,000, many of whom had received free tickets distributed by France to see what Petty later described as “a show” and not a race. Mandatory cautions flew every 25 laps so teams could change tires. Leading the last 11 laps in the Dodge Daytona of Ray Nichels, Richard Brickhouse scored his first and only Grand National victory.

The PDA quickly came apart. But soon NASCAR began paying bonuses to race winners under new series sponsor Winston and established Plan 1C bonuses in the purse for independent drivers, two of the key elements sought by the PDA.

For his part, France was shaken by both Yarbrough’s punch and the realization that he no longer inspired the faith in drivers that had led to 20 years of growth and success. He soon began planning to turn NASCAR leadership over to son Bill France Jr. That came about once the new era focused on the longer high-banked tracks—such as Talladega—in the newly named Winston Cup Series in 1972.

This news is republished from another source. You can check the original article here