A 35-year-old science teacher and father of three, coaching a rag-tag high school baseball team in a small Texas town, makes a deal with his players that if they can somehow win their district championship, he will try out for a Major League Baseball team.

Against all odds, the team turns its season around and makes it to the state playoffs, and the coach — a former Minor League pitcher — winds up throwing 98 mph at the tryout. He is signed by the Tampa Bay Devil Rays, and mere months later, he joins the big league team on the road in his home state, striking out the only batter he faces in his debut.

That’s the story of Jim Morris. It’s a great story. An incredible story. A story so good that Walt Disney Pictures turned it into “The Rookie,” the 2002 film starring Dennis Quaid as Morris. It became the fourth-highest-grossing baseball movie of all-time.

“So many times, movies based on a true story get a little stretched out to make it work,” Quaid tells MLB.com, 20 years later. “With this, you didn’t have to. The story was that good.”

But “The Rookie” only scratches the surface of how improbable and auspicious Morris’ story is.

Turns out, the tale of how the movie came together is as good as the movie itself.

The Agent

Steve Canter read the Baseball Weekly article with his mouth agape and his mind turning.

“This is a movie,” Canter thought to himself.

It was late July 1999, and Canter, a sports agent, was reading an article about Morris while sitting in a hotel room in Knoxville, Tenn. A player Canter was in town to visit had asked him, “Have you heard about the schoolteacher who throws 98 mph?” Canter hadn’t. Few had. So the player, who was teammates with Morris on Double-A Orlando, tossed Canter a copy of the newspaper.

Canter pored over the story of a left-handed pitcher getting a second chance at professional baseball.

Morris had originally been a first-round pick of the Brewers in the January phase of the 1983 Draft, but he had trouble corralling his fastball and staying healthy and didn’t advance above A-ball. He was told by the doctor who surgically removed most of his deltoid muscle in his throwing shoulder in 1989 that he would never pitch again.

So Morris had gone back home to Texas and studied to become a teacher. He got a job teaching physical science at Reagan County High School in Big Lake — a football-obsessed town of fewer than 3,000 people. For the 1999 season, Morris assumed coaching duties of a baseball team that had won a grand total of three games over the previous three seasons.

After two losses to start the year, Morris gave the kids a pump-up speech about following their hopes and dreams. But the players had sensed that Morris, who regularly threw them batting practice, still had a live enough fastball to pursue a dream of his own.

If the Rays call you up to the big leagues, I promise you we’re going to make a movie about your life, and you’re never going to have to worry about being able to take care of your family again.

Steve Canter

That’s how the bet came about. And when Reagan County won the district title for the first time in school history, Morris had to fulfill his end of the deal.

Morris attended an open tryout for the Devil Rays — then in just their second season of existence — in Brownwood, Texas. When he hit 98 mph on 12 straight pitches, the scouts double-checked their radar guns to confirm what they had seen was real. Two days later, Morris threw for the team again and was again in the mid-90s. The team didn’t care about Morris’ age. He was left-handed, throwing gas and healthy. The Devil Rays signed him up quick, and he was in Double-A within a month.

Canter couldn’t believe what he was reading.

“Do you want to meet him?” the player asked.

“Of course.”

Minutes later, Morris entered the room. He was far away from his family, yet closer to the big leagues than he had ever been in his first go-around with professional baseball. That very night, he had been informed that he was to report to Triple-A the next day.

And now Canter was telling him the ride could get even crazier.

“You’re going to Triple-A tomorrow, you’re playing for an organization that’s in last place, and you’re throwing the baseball really, really well,” Canter told Morris. “If you pitch well in Triple-A, the Rays are going to call you up to the big leagues. And if the Rays call you up to the big leagues, I promise you we’re going to make a movie about your life, and you’re never going to have to worry about being able to take care of your family again.”

People promise things. Agents, especially, promise things. Morris had no representation and did not know what to make of this stranger suddenly promising him the world.

He looked at Canter incredulously.

“Man, I’m old and I’m fat and I don’t need an agent,” Morris thought to himself. “This is just a lark.”

But Canter pressed on.

“How many surgeries have you had?” Canter asked.

“Like five,” Morris replied.

“You’ve had five arm surgeries, and you’re 35 years old,” Canter said. “I hate to tell you this, but you could end up hurting your arm again. But you’re going to make your money off the field, and it’s going to be off your story.”

Canter gave Morris a blank contract to consider. Morris shoved it in his suitcase that night and headed off the next morning to Durham, where more eyes would be upon him.

The Teammate

In the waiting room at this doctor’s office, Mark Ciardi read the small item in the “Scorecard” section of Sports Illustrated.

“Jim Morris is the most improbable story to hit the Durham Bulls since Nuke LaLoosh,” the blurb read. “Less than three months ago, Morris was a 35-year-old physics and chemistry teacher at Reagan County High in Brownwood, Texas. Today he’s a few good innings from making the Show.”

Ciardi was instantly enthralled. A former professional pitcher himself, Ciardi knew what it was like to chase that big league dream. And this story about a teacher-turned-pitcher was exactly the sort of story Ciardi, who was now trying to make a name for himself in Hollywood as a film producer, would love to tell on the silver screen.

Then Ciardi got further along in the article.

“A first-round Draft pick of the Milwaukee Brewers in ’83 who threw only 203 pro innings …”

Ciardi’s heart skipped a beat. His eyes zeroed in again on the name.

“Oh my God,” he thought to himself, “that Jimmy Morris?”

Ciardi wasn’t just reading a feel-good story about a grown man given a second chance at realizing a childhood dream; he was reading about his former teammate and Spring Training roommate. Morris and Ciardi had both been drafted by the Brewers in ’83 and pitched together in Rookie ball in Paintsville, Ky., and in A-ball in Beloit, Wis.

Unlike Morris, the right-handed Ciardi had reached the big leagues, albeit briefly. He was a so-called “cup of coffee guy,” having made four appearances for the Brewers in 1987. He didn’t get the call to the Majors the following year. And when it became clear to him that he simply wasn’t in the team’s plans in ’89, he called it a career.

Ciardi, it turned out, had a pretty good backup plan. He spent seven years in Europe as a fashion model, doing photoshoots and commercials.

Now, Ciardi had taken what money he had saved and, with working partner Gordon Gray, started a production company out of an L.A. garage. Until he read about Morris in SI, he was not inclined to focus on sports movies. But this bit of kismet was impossible to ignore.

So Ciardi tried to reach his old teammate by contacting the Durham Bulls. Trouble was, so did everybody else. Morris’ story had now reached enough eyes that he was getting inundated with people who suddenly wanted to work with him. One agent had even promised him a chance to play golf with Tiger Woods.

Morris had enough on his plate, still adjusting to being away from his family and figuring out what to make of his bizarre baseball opportunity. Canter had seemed trustworthy, so Morris gave him a call.

“I signed the contract,” Morris remembers telling his new agent. “I FedEx’d it to you. Now please, just make the calls stop.”

Canter did as advised. But soon, he would make the call that would keep Morris’ story going.

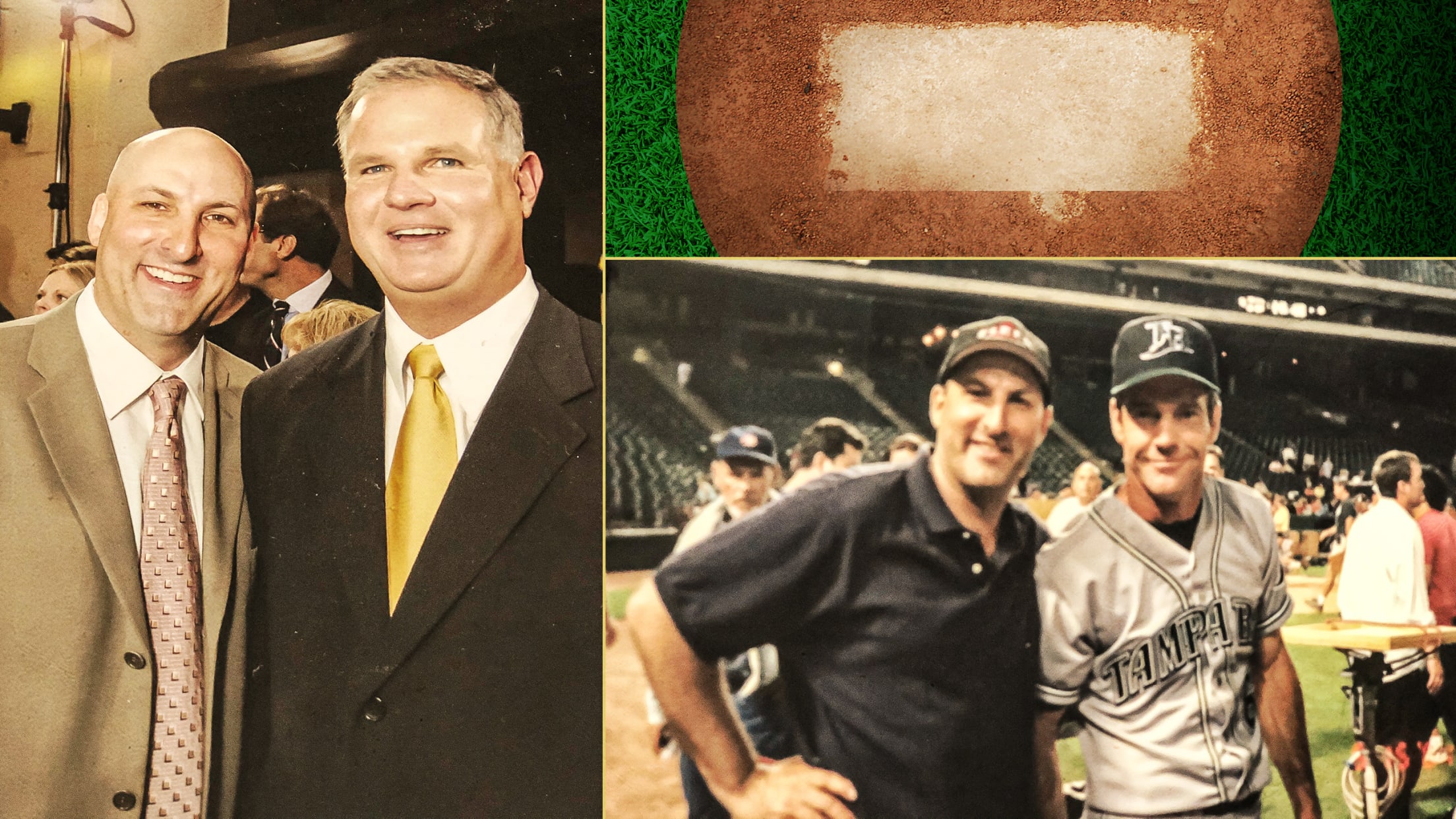

Canter and Morris, left; Canter with Quaid on set, right. (Photos courtesy of Steve Canter)

The Save

The problem with leaving your job, your wife and your three kids to play Minor League Baseball is the whole money thing.

In the summer of 1999, Jim Morris and his family didn’t have much of it. Morris felt he owed it to himself to give baseball another whirl. But after a month or so of puny paychecks and neglected responsibilities back home, the situation was rapidly becoming untenable.

Canter has a memory of Morris calling him soon after he became Morris’ representative and the pitcher telling him, “They’re fixing to take the furniture at my house back in Texas. My wife is telling me I’m going to have to come home to take a teaching job if we don’t get some money really fast.”

Was it really that bad?

“It was very close to being that bad, yes,” Morris says now. “I was extremely serious about going home. My faith plays a big role in the decisions I make, and basically, my prayer was, ‘God, if this is what you want me to do, you’ve got to let me know.’”

Canter let some contacts at various sporting goods manufacturers know about Morris and his unique story.

That’s where the unheralded, unscripted hero of “The Rookie” came into play.

Chuck Schupp was in the midst of what would be a 35-year career as a player relations representative with Louisville Slugger. His job, which he would go on to serve for Marucci Sports after retiring from Louisville Slugger in 2014, was to sign players to personal services contracts, providing them with additional cash in exchange for using Louisville Slugger products.

At that time, Schupp’s clients included some of the biggest names in baseball — Jason Giambi, Manny Ramirez, etc. And his clients were exclusively Major Leaguers.

So when Canter called Schupp with a request that he consider signing a 35-year-old Triple-A pitcher, well, it was a long shot.

“We never pay players in the Minor Leagues,” Schupp says today. “You only get paid when you get called up and have that exposure.”

But Schupp listened as Canter explained why Morris was a special circumstance. And after reading up a bit more about Morris, Schupp felt compelled to help.

“I’ve always had a soft spot for guys that aren’t the top-tier athlete,” says Schupp. “The guys who have to figure out how to get to the big leagues.”

That was definitely Morris.

Louisville Slugger, historically known as a bat maker, was trying to make a footprint in the glove market. So Schupp offered a deal in which Morris would be outfitted with Louisville Slugger gloves, with financial incentives should he make it to the Majors.

But the key to the deal, from Morris’ perspective, was the upfront signing bonus of $4,000. That amount of money was puny by the standards of a Ramirez or Giambi but life-changing for Morris. It kept this Hollywood-worthy story from becoming a historical footnote.

“That’s more than I made in a month teaching and coaching,” Morris says. “It’s almost more than I made in two months.”

Schupp overnighted the check. And so the story lived on.

“If we had not gotten that deal for him,” says Canter, “he goes home.”

The Debut

Morris did go home to Texas.

But not to Big Lake.

On Sept. 18, he got the call to join the big league club during a road series against the Rangers in Arlington.

Morris’ then-wife, Lorri, and their three kids made the 3 1/2-hour drive from their home to be there that night. They saw Jim for the first time in three months when they peeked into the bullpen before the game.

In the bottom of the eighth inning, with two out, one on and the Devil Rays trailing, 6-1, Morris — wearing his TPX glove manufactured by Louisville Slugger — was summoned from the bullpen to face Royce Clayton, who had been an All-Star two years earlier.

What followed was a four-pitch at-bat, all fastballs clocked at 95 mph or higher. Clayton swung through the first two, fouled off the third, then futilely tried to check his swing on a chest-high heater for strike three.

One batter, one out, one memory to last a lifetime. That his family was able to be there for it just made it all the more special.

“Even all these years later,” Morris says, “I’m like, ‘Did that really happen?’ Everything happened so quickly and drastically.”

But if Morris was blessed to join the team in Texas that day, he was doubly blessed with the next stop on the schedule:

Anaheim.

Morris had just authored a story worthy of Hollywood. And now he was headed there(abouts) to sell it.

I want a movie that’s about a group of kids who are called out before they even started. I also want it to be about someone who took a chance at something, so they don’t wake up and go, ‘Why didn’t I try one more time?’

Jim Morris

The Deal

Shortly before Morris’ debut, Ciardi had proposed the idea of a movie about Morris to an executive at Disney. There was interest, but of course everything was contingent upon Morris actually reaching and pitching in the big leagues.

So every morning in early September, Ciardi would get on his dial-up internet and eagerly check to see if Morris had appeared in the previous night’s Durham Bulls game. Ciardi would live and die with each result, as if Morris were the key player on his fantasy baseball team.

And when Morris did get the call and Ciardi checked Tampa Bay’s Sept. 18 box to see Morris had pitched one-third of an inning with one strikeout, he knew what was at stake.

“We’ve gotta get this,” Ciardi thought to himself.

Morris’ debut, which happened on a Saturday night, attracted national attention on ESPN and other outlets. But these were the days before a story like this would go instantly viral. Ciardi had already had some discussions with Canter about the movie idea, so he was seemingly ahead of the game.

Everything changed, though, when the Devil Rays got to Anaheim. On Monday, Morris did an interview with Bill Plaschke of the Los Angeles Times. The next day, the story was plastered on the sports front under the headline, “Living the Impossible Dream.”

The movie industry was now hip to Morris’ story.

“The whole town went after it,” Ciardi says.

So as if settling into his new role as a Major League reliever weren’t enough of a whirlwind for Morris, now he was the hottest commodity in Hollywood.

“I knew it was time to do the deal,” Canter says.

After becoming Morris’ representative, Canter had assembled a team to help him separately sell the film and publishing rights. Living on Wonderland Avenue in the Hollywood Hills, his neighbors included Neve Campbell, Werner Herzog and Alicia Silverstone, among others. It helped him develop contacts in the movie industry. He was connected with Patti Felker, a preeminent entertainment lawyer who became the point person for the slew of offers that would arrive in the week after Morris made it to the Majors.

In the mornings before Morris had to get to Angel Stadium, he and Canter visited or had phone calls with executives from Universal, Paramount, Sony and other production companies to listen to their ideas of how best to bring his story to the screen.

Generally, Morris hated what he heard. One group wanted the movie to take viewers into the big league clubhouse, with subplots about mistresses and drugs.

“They wanted to change this or change that, and I was uneasy with it,” Morris says. “They were trying to make it more of a mature movie, and I didn’t want any part of it. That’s not what it was about.”

The final visit was to the Walt Disney studio in Burbank. Upon arrival, Canter turned to Morris and asked, “What do you want out of your movie?”

“I want a movie that’s about a group of kids who are called out before they even started,” Morris replied. “I also want it to be about someone who took a chance at something, so they don’t wake up and go, ‘Why didn’t I try one more time?’”

Before entering the meeting, Morris and Ciardi saw each other in the parking lot — their first face-to-face since A-ball in Beloit, 14 years earlier.

“We just started laughing,” Ciardi recalls. “I gave him a big hug and we looked at each other like, ‘What the [expletive] is happening here?’”

Disney had assembled some powerful people in the room for the Morris meeting, including studio heads Joe Roth and Dick Cook. When the team presented its pitch, it was as if Morris was hearing his conversation with Canter about his goal for the movie repeated back at him.

“I was pretty much sold,” he says, “before we walked out of the office.”

But much to Ciardi’s dismay, Canter and Morris left without agreeing to a deal. Canter wisely decided to let the situation simmer for a few more days to ensure he received the best offer he could.

That Friday, after Morris and the Rangers had traveled to New York for a series with the Yankees, Canter posted up in Felker’s office and made it known that he would be fielding the final offers for the movie rights.

“Disney,” Canter says, “came in with the most aggressive offer.”

Canter declined to publicly disclose the financial details of the film deal and the separate publishing deal he later negotiated for Morris’ first book, “The Oldest Rookie,” which was co-written with Joel Engel.

Suffice it to say, though, that Canter’s promise from back in that hotel room in Knoxville was fulfilled:

Jim Morris would never have to worry about money again.

Center: Morris during “The Rookie” publicity tour. Photo courtesy of Steve Canter.

The Movie

Dennis Quaid didn’t know Jim Morris’ story before he received the Mike Rich-penned script of “The Rookie” from his agent. But as he read it, he felt a connection to it.

“This story,” Quaid says, “kind of reflected my story.”

In the 1990s, Quaid’s acting career, which had included starring roles in “Innerspace,” “Great Balls of Fire!” and “The Big Easy,” hit a lull. He went to rehab for a cocaine addiction and also battled an eating disorder after losing 40 pounds to play Doc Holliday in 1994’s “Wyatt Earp.”

He saw “The Rookie” as his chance to reclaim lost ground.

“Jimmy got a second chance to go out there and really make a run at being a professional player,” Quaid says. “And my career, I don’t know if you want to say it was stalled, but it was kind of rudderless at the time. This film, more than any other, really gave me that second chance.”

Quaid took it seriously. In the five months he had to prepare for filming, Quaid worked with a pitching coach in his front yard and, once a week, at Dodger Stadium.

“I hadn’t been on a mound since Little League,” Quaid says. “Being able to throw on that mound where [Don] Drysdale, [Sandy] Koufax, [Fernando] Valenzuela and all those guys pitched, gosh, it was something special.”

One reason — beyond the dollars — that Morris had felt so comfortable surrendering his life story to Mark Ciardi, Gordon Gray and the Disney team was Ciardi’s baseball background. He knew that aspect of the story would not be cheapened or misrepresented.

When Morris met Quaid, he felt even more comfortable. As a consultant on the set during the filming, Morris regularly had Quaid’s ear.

“If you see anything you don’t agree with,” Quaid told him, “you tell me, and it’s out.”

Morris was able to attend the vast majority of the filming in 2001, because, by that point, his pitching career had ended. He appeared in five games for the Rays in that magical 1999 season and another 16 in 2000. But after signing on with the Dodgers for 2001, he dealt with vision and balance issues in Spring Training and was also going through a divorce from his wife.

“I walked into [then-Dodgers manager] Jim Tracy’s office and said, ‘It’s time for me to go home,’” Morris recalls. “He hugs me and says, ‘If you need anything, call.’ Then he sends me through the clubhouse with the clubhouse kid giving me helmets and bats and balls to hand out to the neighborhood kids when I get home. I got home, got my kids and went to the movie set.”

The movie, which was directed by John Lee Hancock, took four months to film, with another six months of edits. It was in the can just two years after Morris had made his debut — a remarkably quick turnaround by Hollywood standards.

“Everything went right,” Ciardi says. “The whole thing was charmed.”

In the lead-up to the release of “The Rookie” on March 29, 2002, Morris and Quaid did a nine-city press tour on Disney CEO Michael Eisner’s private jet. Disney’s field marketing director, Erin Weisman, coordinated a successful campaign to get kids out to the theaters.

“What they did that was so smart was they invited the local Little Leagues out,” Quaid says. “It was very much a grassroots campaign.”

Disney arranged a dinner in honor of the movie release at the 21 Club in New York, with Hall of Famers Willie Mays and Hank Aaron among the attendees. There was also a screening of the film at the White House for President George W. Bush.

“The magnitude of it all was just crazy,” Morris says. “I was in awe. To go from teaching in a classroom in West Texas with the mesquite and cactus to flying on a Disney jet is beyond a dream.”

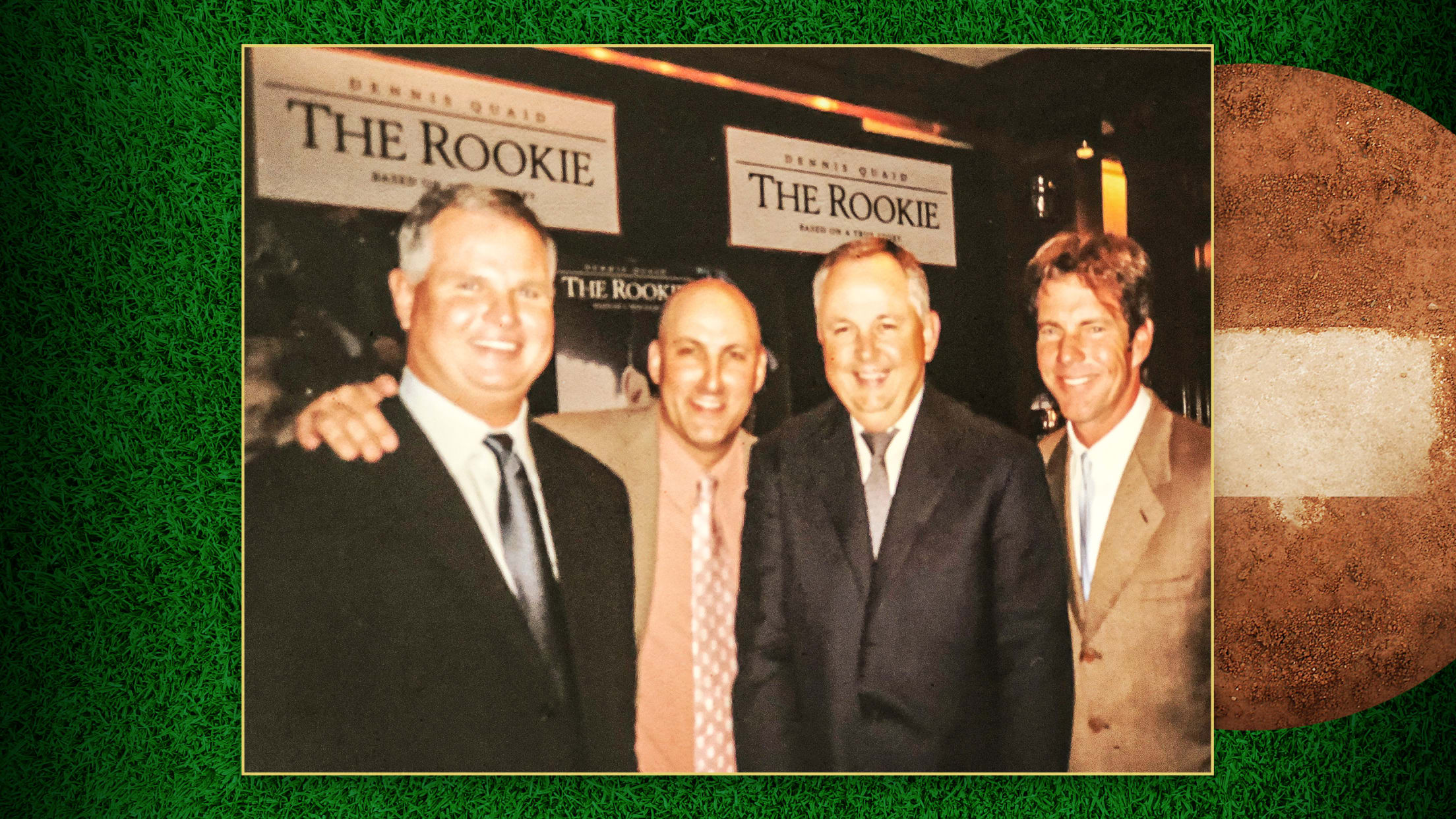

Morris, Canter, then-Disney Studios president Dick Cook and Quaid at “The Rookie” premiere. (Photo courtesy of Steve Canter)

The Aftermath

“The Rookie” had a budget of $22 million and grossed nearly $81 million.

As a result, Jim Morris’ story wound up changing a lot of lives. Not just his own.

Working on the movie and publishing deals remains one of Canter’s most satisfying projects. His instincts while reading that Baseball Weekly article were proven correct.

“I almost went to film school instead of law school, and then I get to do ‘The Rookie,’” Canter says. “It’s almost impossible to get a film made in Hollywood, even if it’s a great story. And this was a great story. It’s amazing how it all worked out. The key to all of this was Jim Morris. He has the power to inspire people.”

He certainly inspired Ciardi, who stumbled across that blurb about his old teammate in Sports Illustrated and wound up with the rights to the movie that launched his production career. Ciardi has gone on to produce many successful sports films for Disney, including “Miracle,” “Secretariat,” “Invincible” and “Million Dollar Arm.”

Not bad for a cup-of-coffee guy.

“It was a big turning point,” Ciardi says. “If it didn’t happen, I don’t know what my life would look like or be.”

“The Rookie” was also a springboard for Hancock. It was his first shot at directing a major feature film. He went on to direct “The Blind Side,” “Saving Mr. Banks,” “The Founder” and others.

Quaid attributes “The Rookie” to relaunching a career that is still going strong. It’s why he calls the experience of making it “magical.”

“The movie is all about gratitude,” he says. “Jimmy and I are still close friends. He came to my mother’s funeral two years ago. … A lot of people wouldn’t be able to handle all of [the attention from the movie]. But I think Jimmy had learned humility and how tentative everything is. It made him grateful. He’s a fine human being. And I ought to know, because I played him!”

Morris parlayed his experience living, making and promoting “The Rookie” into a successful public speaking career. He has circled the globe telling his story and written a second book, “Dream Makers,” which was released last year.

His life has not always been as charmed as it was in that summer of ’99. He believes those physical setbacks he suffered in Spring Training in 2001 were the first signs of the CTE-induced parkinsonism — a condition that causes tremors, slow movement, impaired speech and muscle stiffness — he was diagnosed with in ’13.

“I had gotten to the point where I couldn’t even button the buttons on my dress shirts,” he says.

With the help of a neurostimulator, Morris has overcome that condition. He is remarried, his kids are grown and the high school players who inspired him to launch his second pro baseball career are now all older than he was when he debuted with the Rays.

So the 58-year-old Morris is far removed from the story that changed his life. But the story continues to enrich his life — and the lives of others — in so many ways.

“It was a whole lot shoved into a short period,” he says. “It was just boom, boom, boom. And it was all because of a bet with a group of kids. If it hadn’t been for those kids, I never would have tried.”

This news is republished from another source. You can check the original article here